“Sasaki Maki’s manga taught me what one should say when there's nothing to be said.”

-Murakami Haruki

A man eats spaghetti as jazz notes skim the air. His lost cat enters from off-screen. Unnamed soldiers appear without explanation. Coca Cola and assorted Americana! It sounds like the synopsis of a Murakami Haruki novel. Except it’s not. This tableau is from the panels of Sasaki Maki, experimental manga artist turned children’s author.

Sasaki was born on October 18, 1946 in the suburbs of Kobe to grow up in post-war poverty. By his own admission his family was so poor that they didn’t have shoes to wear, rice to cook or money for school lunches. But his parents ran a printing company and that provided him with scrap paper to feed his imagination. He and the local kids passed around grubby issues of kashihon rental manga that inspired his early scribbles. While everyone else ate up Tezuka Osamu, Sasaki preferred to savor the lighthearted nonsense of Sugiura Shigeru.

Sugiura Shigeru

Sasaki Maki

“Tezuka’s developed themes made it feel like you were reading something really meaty. But his stories are dark, devoid of fun," he recalled in an interview with parenting magazine Fujin no Tomo. "Sugiura, on the other hand, is the kind of thing you read while eating snacks and rolling around the floor. His stuff is pure joy!“

After high school Sasaki enrolled in the Kyoto City University of Arts though soon dropped out when he couldn’t afford the expensive oil paints. Not to worry--his older brother kept him occupied with back issus of Garo, the alternative manga anthology magazine that launched in 1964. He was fascinated by the class struggle of Sanpei Shirato’s Kamui Den and the surreal travelogues of Tsuge Yoshiharu. Reading wasn’t enough. He wanted to draw.

So he put pen to paper and submitted his first work to Garo. He debuted in the November 1966 issue with a short satirical piece, Yoku Aru Hanashi (loosely translated as "Stop Me If You've Heard This One Before"). The biting social commentary opens with a government administrator announcing the legalization of cannibalism as an anti-poverty measure. Before the stuffed suit can finish his spiel, the hungry mob reduces him to a talking skeleton.

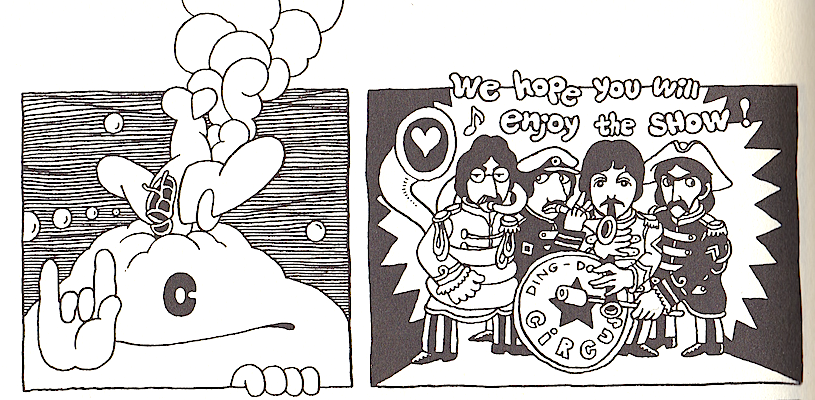

Sasaki made a name for himself the following year when he broke all the narrative rules of manga with Dreams of Heaven. The 19-page experiment has no dialogue and seemingly no plot. He subjects the reader to stream of surrealistic imagery with repeating motifs that include a one-eyed ghost, knife-wielding youth, crucifixes, crashing airplanes and the American flag. Sasaki later explained that he wanted the panels to rhyme, like words in a poem. He claims that he never did layouts because that would invite editor feedback. Instead, he put whatever thoughts flowed through his head onto the page in an improvised, one-man jam session.

Go on, flip through Dreams of Heaven. I'll wait.

Barbed wire fences, gun toting G.I.s, blue jeans and black musicians--the comic captures the disconnect between the resentment Japan felt for the American government and the admiration they held for the all-American lifestyle. The unpopular war in Vietnam further weakened America's pop culture power and strengthened the British Invasion. Sasaki likewise peppers his pages with The Beatles references and, to give it that quintessentially English flavor, the absurd humor of a Mother Goose nursery rhyme.

In 1969 Garo editor Nagai Katsuichi introduced Sasaki to the Asahi Journal, a leftist publication favored by student protestors and other agitated liberals. Sasaki’s nonsense splash pages, a sort of visual jazz with rhyme but no reason, ran between articles that were equally (though unintentionally) nonsensical: “Questioning the Nature of Humanity,” “On the Future of Capitalism,” “The Modern Historical Significance of the Protest Movement.” And so on.

Tezuka bitterly criticized Sasaki’s work in the Asahi Journal as “incomprehensible... manga written by a madman not fit for publication.” Others took the obtuse panels as a challenge and dug for deeper meaning. Sasaki didn’t have it in him to fight against the God of Manga, though he did protest the analysis of his work with The Dog Goes.

To paraphrase manga historian Ryan Holmberg’s essay on the strip, Sasaki viewed any serious analysis of his intent as frivolous and just plain silly. Sasaki began to question his role in writing satire. “What gives me the right to act so high-and-mighty in my manga,” he wondered as ideas and job offers dried up. Conflate this with his disappointment in magazine print quality--the paper was flimsy, the color was always off--and maybe it was time for a change.

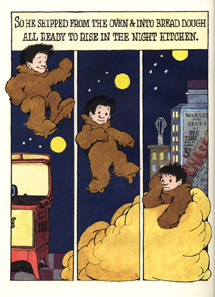

In the Night Kitchen

The Lone Wolf

As luck would have it his former college professor introduced him to children’s book publisher Fukuinkan Shoten. Sasaki was intrigued, though perplexed--how is a picture book different than manga, anyway? But once he saw the word balloons and panels in Maurice Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen, Sasaki figured there was no difference at all.

If he was going to continue to draw manga, albeit in a different format, he might as well use the stable of characters he had accumulated. The shadowy lone wolf, known to end conversations by coughing a dismissive "Keh!" embarked on a search for someone like himself in a world of herbivores. Monsieur Meunière, the walleyed goat, become a traveling black magician. Sasaki’s surreal punch lines, filtered through the mind of a child, started to make sense.

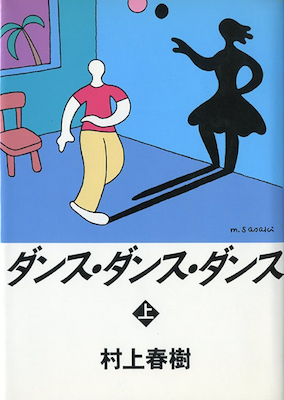

Most people in Japan know Sasaki's art even if they don't know his name. He illustrated the covers for Murakami Haruki's first seven novels in an abstract minimalist style that reflects the unnamed, non-committal protagonists within. Murakami, a long time fan and fellow Kobe native, recognizes Sasaki's influence. If you've ever finished a Murakami story and turned the last page expecting another, you'll know what Murakami meant by "Sasaki Maki's manga taught me what one should say when there's nothing to be said."

Sasaki also provided illustrations for Murakami's short tales, Sheep Man's Christmas and most recently The Strange Library. The English version of Library, staying true to Murakami's lofty image in the west as shoe-in for the Noble Prize in literature, jettisons Sasaki's whimsy for found photographs and an ambitious foldout design by Chip Kidd.

Children's books and illustrations seem to have brought Sasaki the satisfaction that evaded him in manga. As his art and stories became increasingly simplistic, the lines grow round and playful in a style reminiscent of his boyhood hero, Sugiura Shigeru. These days he’s busy with the toddler-friendly book series, Kodomo no Tomo 0.1.2, whose thick cardboard pages perfect for teething.

The other day I went to the bookstore and thumbed through a stack of his picture books. The Two Santas is about an alien Santa that teaches our earth Santa how to walk through walls. His Phantom series treats you to a procession of increasing goofy ghosts. Then there's May I Hug You? where the central conflict, if you can call it that, involves a crocodile asking a penguin for a hug. It gave me the same feeling that Sasaki must have had reading Sugiura's manga as a child--pure joy.

For Sasaki Maki in English, check out Ding Dong Circus and Other Stories translated by Ryan Holmberg and published by Breakdown Press.